Scleroderma isn’t just a skin condition. It’s a silent, progressive autoimmune disease that turns your body’s own defense system against your connective tissues, causing them to harden, thicken, and lose flexibility. This isn’t a rare curiosity-it affects about 300 people per million worldwide, with women between 30 and 50 being four times more likely to develop it than men. What starts as cold fingers turning white or blue can, over years, lead to lung scarring, heart damage, kidney failure, and digestive collapse. And yet, most people-doctors included-don’t recognize it until it’s advanced.

What Actually Happens in Your Body?

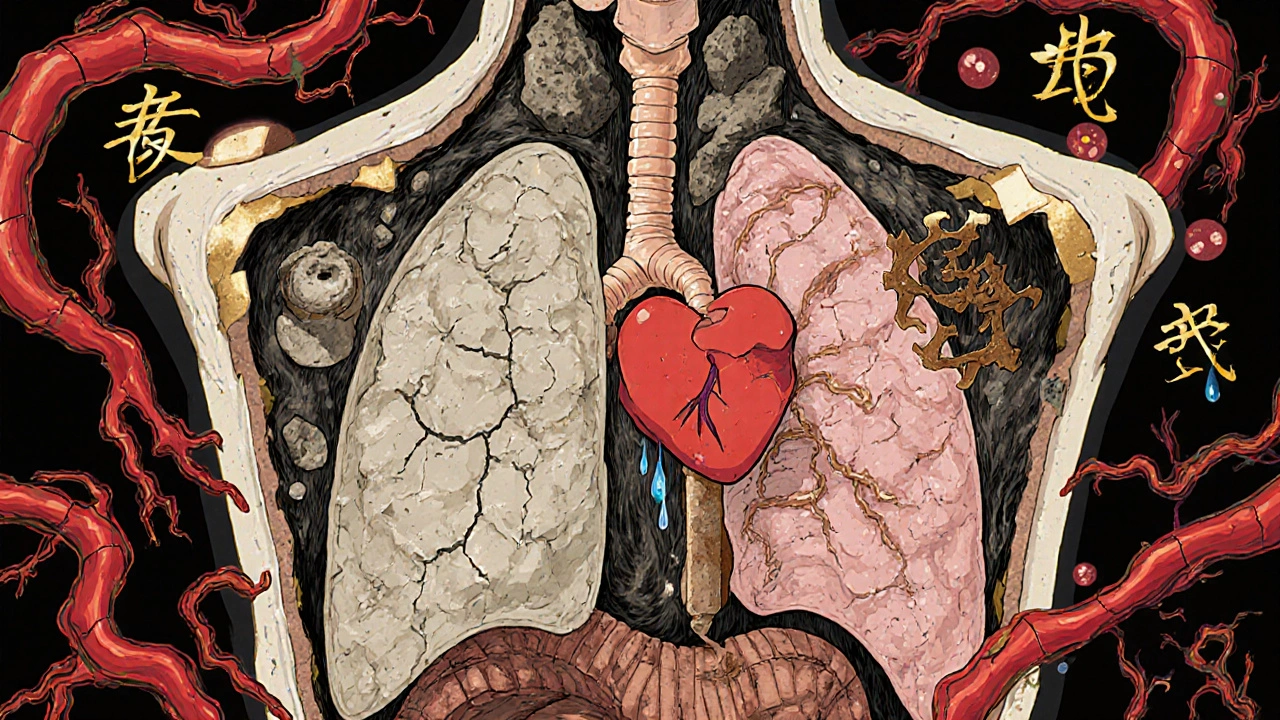

Scleroderma, also called systemic sclerosis, means your immune system goes rogue. Instead of fighting infections, it triggers fibroblasts-the cells that make collagen-to go into overdrive. Collagen is normally a structural protein, like the scaffolding in your skin and organs. But in scleroderma, it piles up like concrete, turning soft tissues stiff. This isn’t just about tight skin. The same process attacks your lungs, heart, kidneys, and gut.

Three key problems happen together: autoimmunity (your immune system attacks you), vasculopathy (blood vessels narrow and get damaged), and fibrosis (tissue hardens). This trio is what makes scleroderma so hard to treat. You can’t just suppress the immune system and call it done. You have to stop the fibrosis, protect the blood vessels, and calm the immune response-all at once.

Two Main Types, Very Different Outcomes

There are two main forms. Localized scleroderma (morphea) only affects patches of skin. It’s rare to progress beyond that. But systemic scleroderma? That’s the dangerous one. It splits into two subtypes: limited and diffuse.

Limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis usually starts with Raynaud’s phenomenon-fingers turning white, then blue, then red when cold. This can happen 5 to 10 years before anything else shows up. Over time, skin thickens on the fingers, face, and forearms. The heart and lungs are still at risk, but progression is slow. Many live 20+ years with it.

Diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis hits harder and faster. Skin thickens rapidly over the hands, arms, chest, and even the trunk. Within 3 to 5 years, it can lead to serious organ damage. About 80% of these patients develop lung fibrosis. One in three gets pulmonary arterial hypertension. Survival rates drop to 55-70% at 10 years.

How Do Doctors Diagnose It?

There’s no single blood test for scleroderma. Diagnosis is a puzzle. Doctors look at symptoms, physical signs, and antibody patterns.

Raynaud’s phenomenon is the earliest red flag. Over 90% of systemic scleroderma patients have it. Sclerodactyly-tight, shiny skin on the fingers-is present in 95%. Nailfold capillaroscopy (examining tiny blood vessels under a microscope) often shows abnormal, enlarged capillaries, a telltale sign.

Antibodies are the next clue. Anti-Scl-70 (topoisomerase I) shows up in 30-40% of diffuse cases and means higher risk for lung scarring. Anti-centromere antibodies (ACA) appear in 20-40% of limited cases and usually mean slower progression. Anti-RNA polymerase III is linked to rapid skin changes and a higher chance of cancer. Almost everyone with systemic scleroderma tests positive for ANA (antinuclear antibodies).

But here’s the catch: patients see an average of 3.2 doctors over 18 months before getting the right diagnosis. Symptoms like fatigue, heartburn, or stiff fingers get dismissed as stress, aging, or arthritis. By the time the skin tightens or lungs weaken, it’s often too late for early intervention.

Why Is Treatment So Limited?

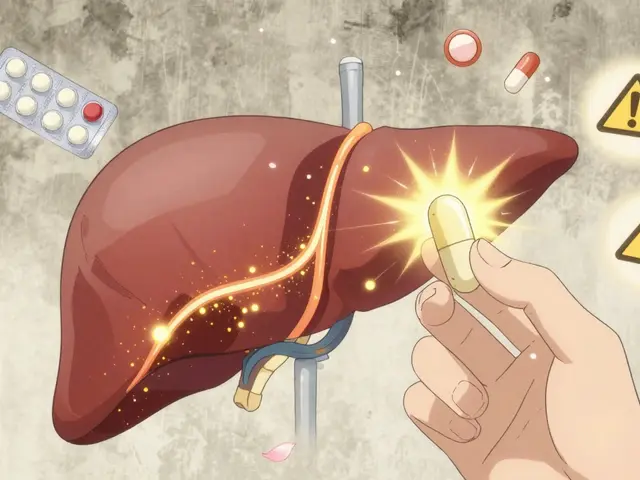

There are no FDA-approved drugs that cure scleroderma. Almost all treatments are borrowed from other diseases. Immunosuppressants like mycophenolate or cyclophosphamide are used for lung fibrosis, but they only help about 40-50% of patients. Skin thickening? Only 30% show meaningful improvement after a year of treatment.

The big breakthrough came in 2021 when the FDA approved tocilizumab for scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease. It’s the first drug specifically cleared for this complication. But it doesn’t fix skin or blood vessel damage. It’s a partial win.

For Raynaud’s, calcium channel blockers like nifedipine help widen blood vessels. Digital ulcers (painful sores on fingers) require specialized wound care, sometimes daily. For pulmonary hypertension, drugs like bosentan or riociguat are used. But none stop the disease itself.

The biggest problem? Fibrosis is stubborn. Once collagen builds up, it’s hard to reverse. Current drugs slow it down, but they don’t stop it. That’s why researchers are now testing drugs that target fibrosis pathways directly-tyrosine kinase inhibitors, B-cell depleting therapies, and even stem cell transplants.

Life With Scleroderma: The Real Daily Struggles

People with scleroderma don’t just have a medical condition. They have a lifestyle overhaul.

Hand contractures make simple tasks impossible. Over 78% of patients struggle to button shirts, open jars, or hold a toothbrush. Many use adaptive tools-grippers, button hooks, electric can openers. Gastrointestinal issues affect 90%. Severe reflux, bloating, and difficulty swallowing mean dietary changes, multiple daily medications, and sometimes feeding tubes.

Fatigue hits 70% of patients. It’s not just tiredness. It’s bone-deep exhaustion that doesn’t go away with sleep. Many leave jobs or cut hours. Mental health suffers too. Depression and anxiety rates are double those of the general population.

And then there’s the isolation. Most people have never heard of scleroderma. Friends don’t understand why you can’t hold a coffee cup. Family thinks you’re exaggerating when you say your skin feels like it’s shrinking. Support groups are lifelines. The Scleroderma Foundation’s patient surveys show those who connect with others report far better emotional outcomes.

What’s Changing? Hope on the Horizon

There’s real progress. In 2024, the Scleroderma Research Foundation committed $15 million to fibrosis-targeted therapies. Over 47 clinical trials are active, testing new drugs that block collagen production at the source. One promising area: serum CXCL4, a biomarker that might detect scleroderma before symptoms even appear.

The SCOT trial showed autologous stem cell transplants led to 50% improvement in skin scores after 4.5 years in severe cases. It’s risky, but for some, it’s life-changing.

Telemedicine is helping too. Stanford’s program now serves rural patients with monthly virtual visits. Early results show a 32% drop in hospitalizations. That’s huge for people who live hours from a specialist.

But access remains a problem. Only 35% of U.S. patients get care at one of the 45 designated scleroderma centers. Most are in big cities. If you’re in rural Australia, Canada, or the Midwest U.S., you’re likely seeing a general rheumatologist who’s never treated more than a handful of cases.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you have Raynaud’s, especially with skin changes or unexplained fatigue, don’t wait. See a rheumatologist. Ask for ANA, anti-Scl-70, and anti-centromere tests. Request a nailfold capillaroscopy. Keep a symptom journal-note cold triggers, skin tightness, heartburn, shortness of breath.

Protect your hands. Wear gloves in cold weather. Avoid smoking-it worsens blood vessel damage. Use moisturizers daily. Keep your skin soft.

Find a specialist center if you can. Johns Hopkins, Stanford, and the University of Michigan have multidisciplinary teams: rheumatologists, pulmonologists, cardiologists, GI experts, and physical therapists-all working together. Patients there report 68% better symptom control than those seeing general rheumatologists.

And if you’re diagnosed-know this: you’re not alone. The science is moving. Treatments are improving. And every person who speaks up, tracks symptoms, and asks for better care helps push the field forward.

Jennifer Stephenson

November 16, 2025 AT 05:36My grandma had this. Skin like parchment. Couldn't hold a cup. Doctors shrugged for years.

Woke up one day and her fingers were locked. No one knew what to do.

Just... kept going. That's all.

It's not rare. It's just ignored.

Laura-Jade Vaughan

November 17, 2025 AT 00:21Okay but like… did you know scleroderma is basically the body’s version of a bad Tinder date? 🤡

It says ‘I care’ but then just… locks you in a basement of collagen and calls it love.

Also, tocilizumab? The only drug that didn’t ghost us. 🙏 #SclerodermaWins

Vera Wayne

November 18, 2025 AT 13:59Thank you for writing this. So many people think it’s just ‘dry skin’ or ‘old age.’

My sister was misdiagnosed for 22 months. She had Raynaud’s since she was 21, but no one connected it to anything serious.

When she finally got the right doctor-nailfold capillaroscopy, ANA, anti-Scl-70-all clicked.

Now she’s on mycophenolate and uses a heated blanket every night.

She can’t button her shirts anymore, but she can still bake pies. That’s her victory.

Don’t wait for the skin to tighten. If your fingers turn colors in the fridge, see a rheumatologist.

And if you’re a doctor reading this? Stop dismissing Raynaud’s as ‘just stress.’

It’s the first scream of a silent storm.

Also, support groups saved us. Find them. Even if it’s just one person who gets it.

And yes, the fatigue? Real. It’s not laziness. It’s your body fighting itself 24/7.

Thank you for naming it.

It’s not just a disease. It’s a whole life rewritten.

And we’re still here. Still baking. Still typing. Still fighting.

Segun Kareem

November 19, 2025 AT 22:13From Lagos to the world-this is the quiet war no one talks about.

They say ‘autoimmune’ like it’s a buzzword. But this? This is your body turning into a prison.

And yet-we survive. We laugh. We hold hands even when our fingers won’t bend.

Science is slow, but it’s moving.

Every trial. Every patient journal. Every voice that says ‘I’m not alone.’

That’s the real cure.

Not just drugs. But dignity.

Keep speaking. Keep tracking. Keep being seen.

Philip Rindom

November 20, 2025 AT 15:37Wow. So… we’re just supposed to believe that one drug approved in 2021 is the ‘big breakthrough’?

Meanwhile, my cousin’s been on a $12k/month infusion for 3 years and still can’t open a jar.

Also, ‘stem cell transplants’? Sounds like sci-fi if you ask me.

But hey, at least we got a fancy name for it now.

…I’m just saying, we’re still waiting for the miracle.

And the ‘support groups’? Cute. But they don’t pay the rent.

Just saying.

Jess Redfearn

November 20, 2025 AT 23:12Wait so if I have cold hands, I have scleroderma? I got that once in winter. Also my dog licked my finger. Coincidence?

Also, why are you all so dramatic? I think it’s just anxiety.

My coworker said her mom had ‘tight skin’ and she just used lotion.

Maybe you just need to chill.

Also, why are there so many tests? Can’t you just Google it?

Ashley B

November 21, 2025 AT 07:16Let me guess-Big Pharma made this up to sell drugs.

They invented ‘fibrosis’ to scare people into taking toxic immunosuppressants.

Look at the numbers: 300 per million? That’s less than lightning strikes.

And ‘anti-Scl-70’? That’s not a real antibody-it’s a marketing label.

They want you to think you’re dying so you’ll take their pills.

And ‘stem cell transplants’? That’s just a cover for experimental gene manipulation.

They’re testing on us.

And why are all the centers in big cities? Because they don’t want rural people to survive.

It’s all a lie. You’re being gaslit.

Go outside. Stop taking meds. Eat raw garlic. You’ll be fine.

And stop believing doctors. They’re paid by the system.

They don’t want you to heal. They want you to stay sick.

Scott Walker

November 21, 2025 AT 07:43My buddy’s wife got diagnosed last year. She’s in Vancouver. Got her on bosentan.

Now she can walk to the mailbox without gasping.

Still can’t hold a coffee cup, but she holds her grandkid. That’s the win.

Also, the virtual care thing? Genius. My cousin in rural Saskatchewan finally got a specialist consult last month.

Just… thank you for sharing this. Real talk. No fluff.

❤️

Sharon Campbell

November 22, 2025 AT 20:40eh i think this whole thing is overblown

my aunt had tight fingers and she just used hand cream

and now she’s fine

also why are we talking about collagen like it’s a villain?

it’s just protein

also why do people think they need a ‘specialist’

can’t you just go to urgent care

also i think they made up the 300 per million thing to sell books

and who even is the scleroderma foundation

probably just a cult

idk man

just sayin

sara styles

November 23, 2025 AT 06:46Let me tell you something nobody else will: the entire scleroderma narrative is a controlled distraction.

They don’t want you to know that fibrosis is caused by EMF radiation from 5G towers.

It’s not collagen-it’s nanotech particles injected via vaccines.

Anti-Scl-70? That’s a marker for bio-chip activation.

And the FDA-approved drug? It’s laced with lithium to suppress awareness.

Look at the timeline: Raynaud’s appears after a vaccine. Then skin thickens. Then ‘lung fibrosis.’ Coincidence? No.

They’ve been testing this on women 30-50 because that’s the demographic most likely to believe ‘doctors’.

And the ‘support groups’? They’re fronts for data harvesting.

They’re tracking your symptom journals to predict when you’ll ‘break’.

And the stem cell trials? They’re not healing you-they’re harvesting your cells for AI training.

They don’t want you to know you can reverse it with lemon water and moonlight.

But now you do.

And now they’ll silence this comment.

Watch.

They’re already deleting it.

Brendan Peterson

November 24, 2025 AT 04:56Interesting breakdown, but the stats feel cherry-picked.

For example, ‘80% develop lung fibrosis’-in what cohort? All diffuse patients? Only those with anti-Scl-70?

And ‘55-70% survival at 10 years’-what’s the baseline? Age? Comorbidities?

Also, tocilizumab is approved for ILD, but it’s not a cure. That’s not a breakthrough-it’s a band-aid.

And the stem cell trial? SCOT was a phase 3 trial with high mortality risk. It’s not for everyone.

People need context, not soundbites.

Also, ‘35% get care at centers’-that’s a systemic failure, not a patient problem.

Just saying. Data matters.

Jessica M

November 24, 2025 AT 12:41As a registered nurse who has worked in rheumatology for 18 years, I can confirm: early detection saves lives.

Raynaud’s is not a ‘cold sensitivity’. It is a vascular red flag.

Nailfold capillaroscopy is underutilized and non-invasive. Every patient with persistent Raynaud’s should have one.

Anti-centromere does not mean ‘mild’-it means ‘slow progression, but still life-altering’.

Patients with diffuse disease need multidisciplinary care: pulmonology, cardiology, GI, rehab.

And yes-support groups reduce depression scores by 40% in longitudinal studies.

Do not dismiss fatigue. It is neuroimmune, not psychological.

Moisturizers are not optional. They prevent fissures and infection.

Smoking cessation is non-negotiable. Vascular damage accelerates 3x.

And to physicians: if you see a patient with unexplained dysphagia or elevated BNP, think scleroderma.

It is not rare. It is underdiagnosed.

And every minute of delay costs function.

Thank you for this accurate, compassionate summary.

Erika Lukacs

November 25, 2025 AT 08:38It’s fascinating how the body, in its attempt to heal, becomes its own undoing.

Collagen, the very substance that holds us together, becomes the chain that binds us.

Is this not the ultimate irony of biological systems?

Self-preservation, corrupted into self-annihilation.

And yet, we persist.

Not because we are strong.

But because we are stubborn.

And perhaps that is the only medicine left.

Rebekah Kryger

November 26, 2025 AT 10:31Okay but ‘fibrosis’ is just a buzzword. It’s basically scar tissue. We’ve known about that since the 1800s.

And ‘vasculopathy’? That’s just blood vessel damage. Big whoop.

Why are we treating this like a new alien disease?

It’s just chronic inflammation + collagen overload.

Also, why is everyone so obsessed with ‘antibodies’? ANA is positive in 30% of healthy people.

And ‘stem cell transplants’? That’s just chemo with a fancy name.

Also, why are you all acting like this is a mystery? It’s not. It’s autoimmune. We’ve got 50 of those.

Stop dramatizing.

It’s just another autoimmune disorder.

And yes, I know the stats. I read the paper.

It’s not special.

Vera Wayne

November 26, 2025 AT 13:42Thank you, Jessica M. You just said what I’ve been screaming into the void for years.

My sister’s rheumatologist didn’t even know what capillaroscopy was until she brought the paper.

And yes-fatigue isn’t ‘just tired’. It’s the immune system burning through every calorie just to keep the lights on.

And I’m so glad someone said it: moisturizers aren’t optional.

My sister’s hands cracked open last winter. She got a staph infection.

It took three rounds of antibiotics.

Just… keep saying it.

Because nobody else will.

And if you’re reading this and you’re scared?

You’re not alone.

We’re here.

And we’re not letting this be ignored anymore.