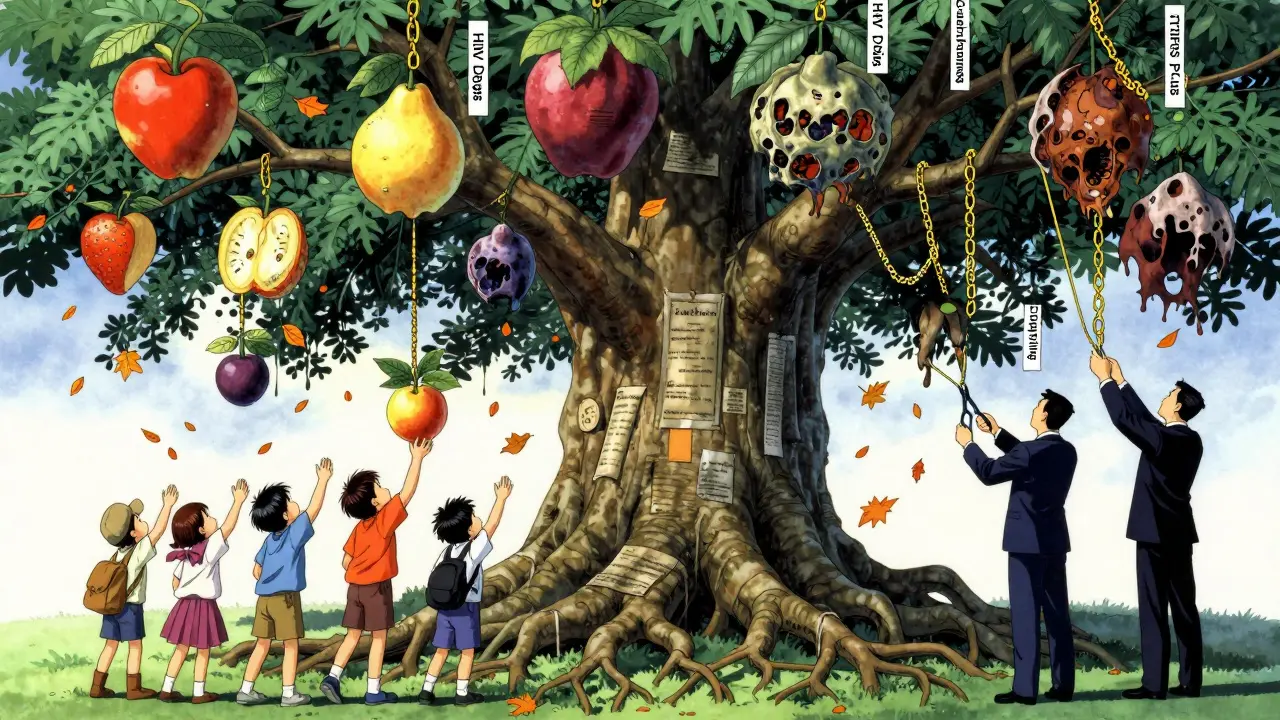

On January 1, 1995, a global rule changed how millions of people access medicine. The TRIPS Agreement - part of the World Trade Organization’s founding treaties - forced every member country to grant 20-year patents on pharmaceuticals. For the first time, countries like India, Brazil, and South Africa could no longer make cheap versions of life-saving drugs. The goal was to protect innovation. The result? A system that made medicines unaffordable for billions.

What TRIPS Actually Does

The TRIPS Agreement doesn’t just cover patents. It sets minimum standards for copyright, trademarks, and industrial designs. But its most damaging impact is on drugs. Article 33 says every patent must last at least 20 years from the filing date. Article 27 says pharmaceutical compounds - even if they’re just slight modifications of existing ones - must be patentable. This meant that before TRIPS, countries could copy drugs freely. After TRIPS, they couldn’t. Before 1995, India made 60% of the world’s generic HIV drugs. A year of antiretroviral treatment cost $10,000 in the U.S. In India, it cost $350. After TRIPS, India had to stop. By 2005, when it fully complied, the same treatment jumped to $1,000. That’s not innovation. That’s monopoly pricing.The Flexibilities That Don’t Work

TRIPS wasn’t meant to be a death sentence for poor countries. Article 31 lets governments issue compulsory licenses - allowing local manufacturers to produce generic versions without the patent holder’s permission. The 2001 Doha Declaration confirmed this right, saying public health emergencies override patent rules. But here’s the catch: Article 31(f) says those generics can only be made for the domestic market. So if you’re a small country like Rwanda with no drug factories, you’re out of luck. That’s why the WTO added Article 31bis in 2005 - a work-around to let countries import generics made under license. Sounds fair, right? It’s not. The system requires 78 separate steps. Importing countries must prove they have no manufacturing capacity. Exporting countries must issue a license with exact product specs. Both must notify the WTO 15 days before shipment. The patent holder gets paid - but how much? No fixed rate. That means delays, legal threats, and political pressure. Only one country has ever used it: Rwanda, in 2008. It imported HIV medicine from Canada. The process took four years. Médecins Sans Frontières called it “unworkable.” A decade later, no other country has tried again.Why No One Uses the Flexibilities

A 2017 study of 105 low- and middle-income countries found that 83% had never issued a single compulsory license. Why?- They don’t have lawyers or bureaucrats trained in patent law.

- They fear trade retaliation - like the U.S. removing their export benefits.

- Pharmaceutical companies threaten lawsuits.

The Real Barrier: TRIPS-Plus

TRIPS is bad enough. But worse are the TRIPS-plus clauses hidden in bilateral trade deals. The U.S.-Jordan Free Trade Agreement, signed in 2001, extended patent terms beyond 20 years. It blocked generic approval until the patent expired - even if the drug was never sold in Jordan. Similar clauses exist in deals with Morocco, Colombia, and dozens of others. A 2021 WTO report found that 86% of member states have added TRIPS-plus rules through side agreements. These extensions delay generics by an average of 4.7 years. That’s not legal. It’s not fair. It’s just power. The result? An estimated $2.3 billion in lost savings each year across 34 developing countries. That’s enough to treat millions of people with HIV, tuberculosis, or hepatitis C.What’s Working Instead

There’s one bright spot: the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP). Created in 2010, it’s a nonprofit that negotiates voluntary licenses with drug companies. Instead of fighting patents, it asks them to share them. As of 2022, MPP had agreements covering 44 patented medicines. It helped 118 low-income countries get generic HIV, hepatitis C, and COVID-19 drugs. But here’s the problem: it only covers 1.2% of all patented medicines. And 73% of those licenses are limited to sub-Saharan Africa - even though the same diseases exist in Asia and Latin America. Voluntary licenses are great - but they’re not a right. They’re a favor. And companies can take them back anytime.

The COVID-19 Test

When the pandemic hit, the world saw what happened when patents blocked access. Vaccine doses were hoarded. Rich countries bought enough for their populations three times over. Low-income countries waited months. In October 2020, India and South Africa proposed a full TRIPS waiver for vaccines, tests, and treatments. After two years of pressure, the WTO agreed - but only for vaccines. Therapeutics and diagnostics were left out. The waiver allowed countries to bypass patents temporarily. But it required complicated procedures. Only a handful of countries used it. The real winners? Companies that already had deals with the MPP or governments that invested in local production. The lesson? Temporary fixes don’t fix broken systems.The Future: Can TRIPS Be Fixed?

The UN High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines, led by former Nigerian Finance Minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, called TRIPS “an institutionalized system of inequity.” That was in 2016. Nothing changed. Now, the WHO is pushing to expand TRIPS flexibilities to digital health tools - like AI diagnostics and telemedicine platforms. That’s a sign the debate is growing. But the real question is: who decides? Pharmaceutical companies spent $25 billion on lobbying in 2022. Developing countries? They have one lawyer per 100 million people working on IP issues. Without political will, the rules will stay the same. And the cost? Two billion people still can’t get the medicines they need. That’s not a market failure. It’s a policy failure.What Needs to Change

- Remove Article 31(f) - let countries import generics without restrictions.

- Simplify the 31bis system to under 10 steps - not 78.

- Ban TRIPS-plus clauses in all trade deals.

- Give developing countries funding and legal support to use flexibilities.

- Make compulsory licensing a right - not a political gamble.

Can a country legally produce generic drugs even if a patent exists?

Yes. Under Article 31 of the TRIPS Agreement, countries can issue compulsory licenses to produce or import generic versions of patented medicines without the patent holder’s permission - as long as they meet certain conditions, like paying fair compensation and using the drugs mainly for domestic needs. The 2001 Doha Declaration confirmed this right, especially during public health emergencies.

Why hasn’t the Article 31bis system been used more often?

The Article 31bis system is overly complex, requiring over 78 procedural steps across two countries. It demands detailed notifications to the WTO, proof of no domestic manufacturing, and approval from patent holders. The only successful use was Rwanda importing HIV drugs from Canada in 2008 - a process that took four years. Most countries lack legal expertise or fear political backlash from pharmaceutical companies and powerful trade partners.

What’s the difference between TRIPS and TRIPS-plus?

TRIPS sets the global minimum standard for patent protection - 20 years for pharmaceuticals. TRIPS-plus refers to stricter rules added in bilateral trade deals, like extending patent terms beyond 20 years, blocking generic approval until patent expiry, or requiring data exclusivity. These are not required by WTO law - they’re extra burdens imposed by richer countries on poorer ones, reducing access to affordable medicines.

How do patents affect the price of medicines in poor countries?

Patents allow companies to charge monopoly prices. Before TRIPS, generic HIV drugs cost $350 per year in India. After TRIPS, the same drugs cost $1,000 or more. For cancer drugs like imatinib, prices dropped 80% in Thailand after a compulsory license. In some cases, patented drugs cost 1,000 times more than generics. Without generic competition, patients go without.

Why do pharmaceutical companies oppose compulsory licensing?

They argue it undermines innovation by reducing profits. But data shows that most new drugs are developed with public funding - and only a small fraction of patents are truly groundbreaking. Their opposition is often tied to protecting market share. When Thailand or Brazil issued licenses, companies responded with lawsuits and trade threats, not innovation. Their real concern is not innovation - it’s control.

Is voluntary licensing through the Medicines Patent Pool enough?

No. The Medicines Patent Pool covers only 1.2% of all patented medicines, and most licenses are limited to HIV drugs in sub-Saharan Africa. Voluntary licenses depend on corporate goodwill - they can be withdrawn or restricted. They don’t guarantee access during emergencies. Compulsory licensing is a legal right; voluntary licensing is a privilege.

What happened to the 2022 WTO TRIPS waiver for COVID-19 vaccines?

The waiver allowed countries to temporarily bypass patent rules for COVID-19 vaccines - but only vaccines, not tests or treatments. It required complex notifications and didn’t force technology transfer. Only a few countries used it, and production remained concentrated in a handful of factories. The waiver was a symbolic gesture, not a structural fix. It proved that even in a global crisis, the system favors profit over people.

Can least-developed countries ignore TRIPS patent rules?

Yes - until 2033. The WTO granted least-developed countries (LDCs) an extended transition period to implement pharmaceutical patents. As of 2023, 67 of 48 LDCs still lack the legal framework to issue compulsory licenses, despite having the right. Many don’t know how to use it, or fear retaliation. The extension is a lifeline - but only if governments act.

Palesa Makuru

January 3, 2026 AT 10:28Look, I get that patents are a hassle, but if we don't protect innovation, who's gonna spend billions研发 new drugs? You can't just hand out life-saving meds like candy - there's a system, even if it's flawed. Maybe we need better funding models, not dismantling IP. I'm not heartless, I'm just not naive.

Hank Pannell

January 5, 2026 AT 04:42What's fascinating here is the structural asymmetry - TRIPS was framed as a global harmonization tool, but in practice, it became a regulatory capture mechanism. The WTO's architecture privileges capital mobility over human mobility. Article 31bis isn't just bureaucratic - it's epistemologically colonial. It assumes Global South states lack the institutional capacity to self-determine health policy, while simultaneously denying them the legal tools to do so. The real tragedy? We're not talking about efficiency. We're talking about mortality thresholds.

Sarah Little

January 6, 2026 AT 15:36Actually, the 31bis process isn't that complicated - it's just that no one wants to go through the paperwork. And let's be real, the pharma lobbyists are still calling every minister who tries. I've seen the emails. It's not the law. It's the fear.

innocent massawe

January 7, 2026 AT 16:56My cousin in Lagos couldn't afford his hepatitis C meds. He waited 2 years. Then a friend brought generics from India. He's alive now. TRIPS? It's a spreadsheet that forgets people. 😔

veronica guillen giles

January 8, 2026 AT 14:47Oh wow, so the solution is to ignore patents? Brilliant. Let’s just let every country become a pharmacy and call it ‘social justice.’ Meanwhile, the same companies that ‘exploit’ patients are the ones who developed mRNA tech in 18 months. Maybe instead of tearing down IP, we should build better bridges? Or is that too much to ask?

Ian Detrick

January 8, 2026 AT 22:52This isn't about patents. It's about who gets to define human dignity. If a child dies because a drug costs $1,000 instead of $350, that's not a market failure - it's a moral collapse. We built systems to serve people. Now we serve systems. The question isn't 'can we fix TRIPS?' It's 'do we still care enough to try?'

Angela Fisher

January 9, 2026 AT 01:17Okay but what if this is all a setup? What if the WHO, WTO, and Big Pharma are in a secret cabal to control populations? They don't want you healthy - they want you dependent. Look at the numbers: every time a country tries to make generics, someone gets ‘sanctioned’ or ‘investigated.’ Coincidence? Or is this the new eugenics? They’re not selling medicine - they’re selling control. And the MPP? That’s just the velvet glove. Behind it? The iron fist of corporate surveillance. 🕵️♀️💊

Neela Sharma

January 10, 2026 AT 03:30India made the world’s HIV drugs for pennies. Then they were told to stop. Now we’re told to be grateful for voluntary licenses like they’re a gift from a king. But this isn’t charity. This is justice. And justice doesn’t ask permission. It takes the wheel. 🚗💨

Let them sue us. Let them threaten. We’ve survived colonialism. We’ll survive their patents too.