When you buy a bottle of medicine, a ready-to-eat meal, or a jar of lotion, you expect it to be safe. But behind that simple expectation is a complex system of checks - one of the most critical being environmental monitoring. This isn’t just about keeping things clean. It’s about catching contamination before it touches your product - and potentially your body.

Why Environmental Monitoring Matters

Think of your manufacturing facility like a house. If you don’t check for mold in the basement, leaky pipes in the kitchen, or dust under the fridge, problems grow quietly until they’re impossible to ignore. Environmental monitoring is the same idea, but for factories that make things people consume or use on their skin. In pharmaceutical plants, a single airborne spore can ruin a batch of injectable drugs. In food processing, Listeria monocytogenes can hide on a floor drain and contaminate deli meats - leading to deadly outbreaks. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says nearly 87% of foodborne illness outbreaks tied to environmental sources could’ve been stopped with proper monitoring. That’s not a small number. It’s a system failure. The FDA and European regulators don’t treat this as optional. They require it. And if you’re running a facility that makes medicines, food, or cosmetics, skipping environmental monitoring isn’t just risky - it’s illegal.The Zone System: How Contamination Risk Is Ranked

No facility is the same, but every serious operation uses the same basic framework: the Zone System. It divides your facility into four risk levels, and your testing frequency and methods change depending on the zone.- Zone 1: Direct contact with the product. Think slicers, mixers, conveyor belts, packaging surfaces. This is ground zero. If something’s wrong here, your product is compromised. Sampling here happens daily or weekly.

- Zone 2: Near-contact areas. Equipment housings, refrigeration units, nearby tools. Not touching the product directly, but close enough to spread contamination. Tested weekly to monthly.

- Zone 3: Remote but still inside production areas. Forklifts, storage racks, overhead pipes. These are often ignored - until they’re not. A PPD Laboratories study found floors (Zone 3) caused 62% of all contamination alerts.

- Zone 4: Outside production - hallways, restrooms, entryways. Tested monthly or quarterly. Low risk, but still monitored because contamination can migrate.

What You’re Testing For

You’re not just looking for dirt. You’re hunting for specific threats:- Microorganisms: Bacteria like Listeria, Salmonella, E. coli. Mold and yeast in cosmetics or pharmaceuticals. These are the most common culprits.

- Particulates: Tiny bits of dust, fibers, or skin cells. Especially critical in sterile drug production. The FDA requires continuous air monitoring in cleanrooms to meet ISO Class 5 standards.

- Chemicals: Residues from cleaners, lubricants, or heavy metals. Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) testing detects these at parts-per-billion levels.

- Water quality: In pharma, purified water must meet USP <645> standards. Conductivity and total organic carbon (TOC) are measured constantly. In food, it’s about municipal water safety - EPA standards apply.

How Testing Is Done

There’s no one-size-fits-all method. The tool depends on what you’re hunting.- Swabs and sponges: Used on surfaces. Sterile, moistened swabs wipe down Zone 1 and 2 surfaces. They’re sent to a lab for culture growth - takes 24 to 72 hours.

- Air samplers: Liquid impingers suck air through water; solid impactors slam particles onto agar plates. Both give you CFU/m³ - colony-forming units per cubic meter of air. Critical in cleanrooms.

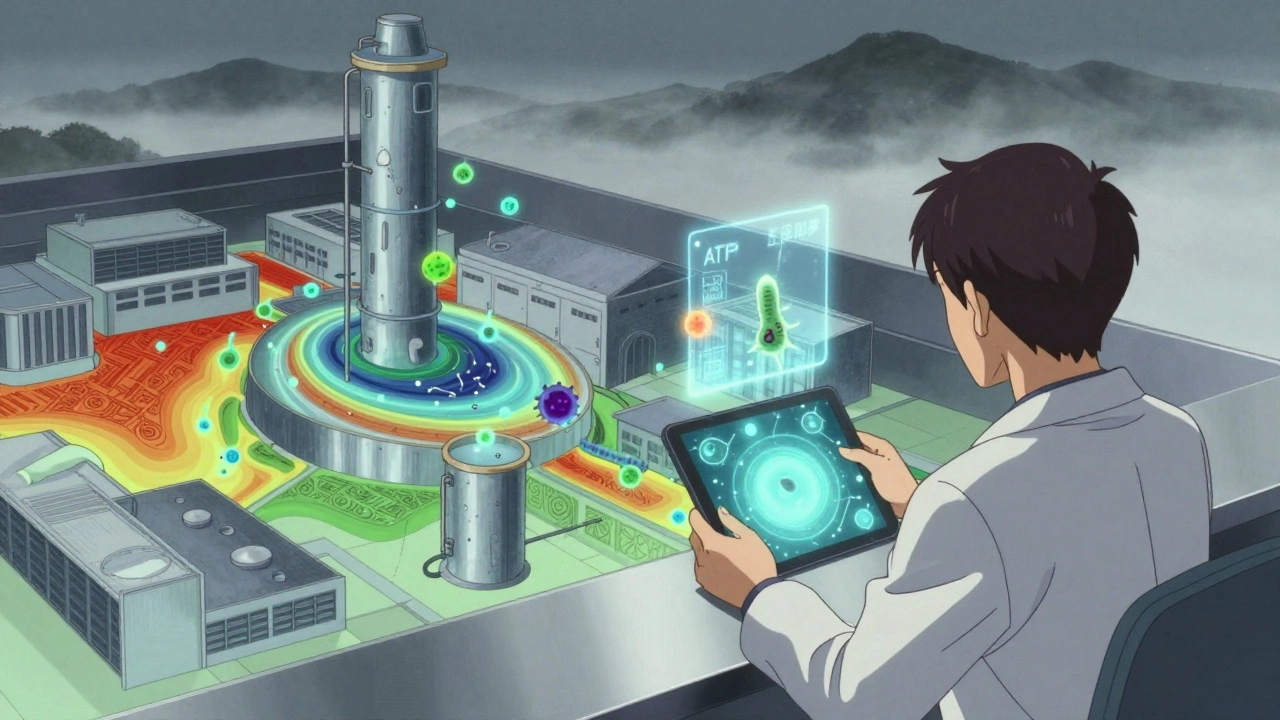

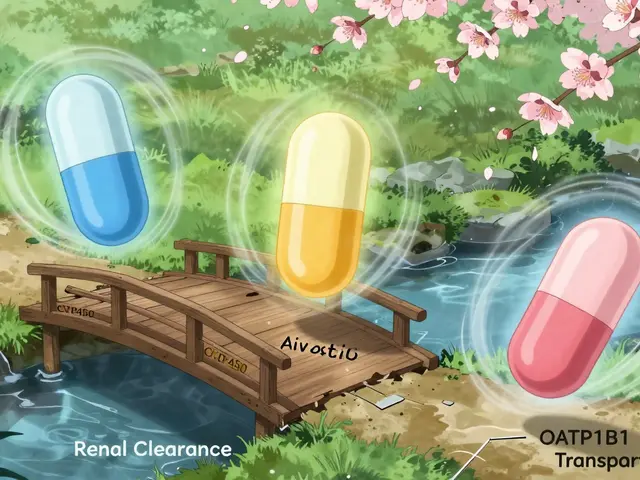

- ATP testing: This is the fast alternative. Swabs detect adenosine triphosphate - a molecule found in all living cells. Results in seconds. FDA data shows facilities using ATP cut turnaround time between production runs by 32%. It doesn’t tell you *what* is there, but it tells you *if* something is there.

- Chromatography (GC, HPLC): Used for chemical residues. If a cleaner leaves behind a toxic compound, this test finds it.

Real-World Numbers and Compliance

Let’s get real about what it costs and what’s expected. - The global environmental monitoring market hit $7.2 billion in 2022 and is expected to hit $12.5 billion by 2027. Pharma leads at 42% of that market. - In the U.S., 98% of pharmaceutical manufacturers have formal environmental monitoring programs. Only 76% of food processors do. - Medium-sized food plants spend $15,000-$25,000 a year on testing supplies and lab services. - FDA requires at least 40 hours of hands-on training before staff can collect environmental samples. - In RTE (ready-to-eat) food plants, Zone 1 must be tested for Listeria at least once a week - under USDA’s Listeria Rule (9 CFR part 430). And here’s the kicker: contamination rates are low - under 0.01% of tests show action-level results. But that’s not because facilities are perfect. It’s because they’ve learned to monitor smartly. The goal isn’t zero contamination. It’s control. Early detection. Prevention.

What’s Changing Now

The game is evolving. - Real-time monitoring: EU GMP Annex 1 (updated August 2023) now requires continuous data trending for temperature, humidity, and particle counts in critical areas. No more manual logs. - Next-generation sequencing (NGS): Instead of waiting 3 days to ID a microbe, labs can now sequence its DNA in under 24 hours. The FDA is pushing for this in their 2023 draft guidance. - AI and analytics: AI tools are starting to predict contamination risks based on historical data, weather, staffing patterns, and cleaning schedules. By 2027, 38% of monitoring systems will use AI - up from 12% in 2022. - Antibiotic-resistant pathogens: 19% of Listeria isolates from food environments now show resistance to multiple antibiotics. Monitoring isn’t just about safety anymore - it’s about public health crises. These aren’t future trends. They’re requirements. If your facility is still using paper logs and sending swabs to a lab every Friday, you’re already behind.Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Most failures aren’t technical. They’re human.- Inconsistent zone classification: One manager says overhead pipes are Zone 3. Another says they’re Zone 1 because they drip. No standard = no control. Create a facility map. Get everyone to agree. Document it.

- Improper sampling technique: If your swab isn’t sterile, or your air sampler isn’t cleaned between uses, you’re contaminating your own sample. CDC guidelines say this happens more than you think.

- Ignoring Zone 3 and 4: Floors, carts, and pipes are where contamination hides. Don’t skip them because they’re ‘not critical.’ They are.

- Not training staff properly: 68% of facilities report inconsistent sampling because staff aren’t trained. Invest in hands-on training. Don’t just hand them a checklist.

- Using ATP as a replacement, not a supplement: ATP tells you if something’s there. It doesn’t tell you what. Use it to speed up cleaning cycles - not to skip lab tests.

Where to Start

If you’re setting up a program from scratch:- Map your facility. Define Zone 1 through Zone 4 with your team. Agree on boundaries.

- Identify your top 3 threats (e.g., Listeria, mold, metal residues).

- Choose your testing methods: swabs, air samplers, ATP, water tests.

- Set sampling frequency: daily for Zone 1, weekly for Zone 2, monthly for Zone 3/4.

- Train your team. 40 hours minimum. Include sterile technique, data logging, and emergency response.

- Integrate your data. Use software to tie swab results, air counts, cleaning logs, and ATP readings into one dashboard.

- Review monthly. Look for trends. If a spot keeps testing positive - fix the source, not just the swab.

What’s the difference between environmental monitoring and product testing?

Product testing checks the final item - the pill, the soup, the cream - for contamination. Environmental monitoring checks the *place* where it’s made: the air, the floors, the equipment. It’s proactive. Product testing is reactive. You want both, but environmental monitoring stops problems before they happen.

How often should I test Zone 1 surfaces?

Daily for high-risk products like ready-to-eat foods or sterile injectables. For lower-risk items, testing 2-3 times per week is acceptable. The FDA requires at least weekly testing for Listeria in Zone 1 for RTE foods. Always base frequency on risk, not convenience.

Is ATP testing enough for compliance?

No. ATP testing gives you quick results - it shows if biological material is present. But it doesn’t identify *what* it is. Regulators require microbial confirmation. Use ATP to speed up cleaning and verify sanitation, but always follow up with lab-based culture tests for pathogens like Listeria or Salmonella.

Why are floors a big problem in contamination?

Floors are Zone 3 - they’re not supposed to touch products. But they’re walked on, cleaned with dirty mops, and often near drains. Studies show floors are the source of 62% of all contamination alerts. A shoe picks up bacteria from a drain, walks across the floor, and transfers it to a cart that touches a conveyor belt. It’s not about the floor being dirty - it’s about how contamination spreads.

What’s the biggest mistake facilities make?

Treating environmental monitoring as a compliance task, not a risk management system. Many facilities collect data but never act on it. If a swab comes back positive, they clean the surface - but never ask why it happened. Was the cleaning schedule wrong? Was the equipment leaking? Was a worker not trained? Real control comes from fixing the root cause, not just wiping it down.

Jay Everett

December 1, 2025 AT 23:08Man, this post is a godsend. I work in a pharma plant and we just upgraded our Zone 1 swabbing to daily + ATP pre-shift. Cut our batch rejections by 40% in 3 months. 🙌

ATP doesn't tell you what's there, but it tells you when to panic. And that's half the battle.

Also, stop treating Zone 3 like it's 'low risk' - our forklift tires tracked Listeria from the loading dock to the packaging line. Took us 6 weeks to trace it. 🤯

मनोज कुमार

December 3, 2025 AT 18:45Zone 4 ignored 90 of facilities. Floor drains = silent killers. ATP false sense security. Culture tests mandatory. FDA dont care about your quick fix. Compliance is not optional. Done.

Shannara Jenkins

December 4, 2025 AT 18:02This is such a clear breakdown - thank you for writing this! I’ve seen so many teams skip Zone 3 because ‘it’s not touching the product’… until it does. And then everyone panics.

Start small: map your facility, get everyone in a room, and just talk about where the dirt *actually* moves. It’s not glamorous, but it saves lives.

You’re not checking boxes. You’re building a safety net. 💪

Elizabeth Grace

December 5, 2025 AT 22:33Ugh. I work at a mid-sized cosmetics plant. We got audited last month. Turned out our ‘Zone 3’ mop bucket was sitting RIGHT under the ceiling vent that feeds the filler room.

They gave us a 48-hour notice to fix it or shut down. We did. But now I’m terrified every time someone walks in with muddy shoes.

Why do we only care when the FDA shows up?

Lynn Steiner

December 6, 2025 AT 02:53Why are we even talking about this? The real problem is that foreign companies are undercutting us with cheaper, sloppier standards. We’re the ones following every rule, paying for all this testing, while some factory in Bangalore ships out contaminated lotion and calls it ‘organic.’

It’s not a monitoring problem. It’s a betrayal of American standards. 🇺🇸

Alicia Marks

December 7, 2025 AT 16:24One sentence: If your cleaning log looks like a grocery list, you’re already behind. Fix the system, not the symptom.

Paul Keller

December 9, 2025 AT 00:16While the data presented here is statistically sound and methodologically rigorous, I must raise a critical epistemological concern: the assumption that environmental monitoring can ever be truly proactive. All monitoring systems, by their very nature, are retrospective - they detect what has already occurred. The notion that we can ‘prevent’ contamination is a comforting illusion, a technocratic fantasy born of overconfidence in our ability to quantify chaos.

Perhaps the more honest approach is to accept that contamination is inevitable - and focus instead on resilience, redundancy, and rapid response. The goal should not be zero contamination, but zero impact.

And yet… I still check the swabs every morning. Because hope is a habit we can’t afford to break.

dave nevogt

December 9, 2025 AT 13:43I’ve spent 18 years in cleanroom tech, and I’ve seen every trend come and go. ATP? Great for speed. NGS? Game changer. AI predicting contamination? Still feels like magic smoke.

But here’s what no one talks about - the human factor. The tired worker who skips a swab because they’re on break. The new hire who thinks ‘Zone 2’ means ‘somewhere near the machine.’ The manager who says ‘we’ll fix it next quarter’ - and then retires before it happens.

Technology doesn’t fail. People do. And no algorithm can fix a culture of apathy.

Train like your life depends on it. Because it does.

Steve Enck

December 10, 2025 AT 11:02The statistical framing here is superficial. You cite a 62% contamination rate from Zone 3, but fail to contextualize the sample size, sampling bias, or temporal variance. The FDA’s 40-hour training requirement is not a benchmark - it is a bureaucratic artifact designed to inflate compliance costs, not improve safety.

Moreover, the conflation of ‘compliance’ with ‘safety’ is a dangerous semantic sleight-of-hand. A facility may be 100% compliant and still produce contaminated product. The metrics are performative, not predictive.

True risk management requires philosophical humility - not more swabs.

Joel Deang

December 11, 2025 AT 12:47yo i just started at a food plant and this post is wild. i thought we just wiped stuff down and called it a day 😅

turns out my shoes are basically listeria taxis and the floor is a crime scene. i’m now obsessed with zone maps.

also, why does everyone keep saying ‘culture tests’ like it’s a secret handshake? i think i need to go to school.

anyone got a ‘environmental monitoring for dummies’ pdf? 🙏

Arun kumar

December 11, 2025 AT 13:54India has same problem. Many small pharma units skip Zone 3. They think clean room is only where machine is. But dust from outside enter through door. Workers wear same shoes inside and outside. No training. No money. But people still take medicine. Sad.

Zed theMartian

December 13, 2025 AT 13:50Oh wow. A 12-page manifesto on how to wipe a floor. How noble. How… *necessary*.

Meanwhile, the real threat is corporate greed - companies that prioritize profit over people, and then outsource blame to ‘untrained staff’ and ‘inadequate budgets.’

Environmental monitoring? Please. What we need is a revolution. Burn the cleanrooms. Let nature reclaim the machines. Let the spores win. Maybe then we’ll stop pretending we can control the uncontrollable.

Or maybe… just maybe… we should stop making so much stuff in the first place.

Ella van Rij

December 14, 2025 AT 02:10Wow. 12.5 billion dollar market? And you’re telling me we still need *swabs*? How quaint. I’m sure the FDA’s 1987 guidelines are still state-of-the-art. /s

Meanwhile, I’m over here using a drone with a UV-C wand and real-time DNA sequencer in my garage. But sure, keep sending your swabs to the lab on Friday. I’ll be here, watching the AI predict your next contamination event… while you’re still printing paper logs.

ATUL BHARDWAJ

December 14, 2025 AT 09:43Zone 4 is important. We had incident. Shoe from outside. Brought in mold. Contaminated 3 batches. Now we have boot washer. Simple. Cheap. Effective. No need for fancy tech. Just discipline.