Most people don’t think twice about taking antibiotics. A sore throat, a sinus infection, a urinary tract infection - pop a pill, feel better in a few days. But for some, that simple cure can lead to something far worse: C. difficile colitis. It’s not rare. It’s not rare at all. Every year in the U.S., half a million people get infected with Clostridioides difficile, and nearly 30,000 die from it. And the root cause? Often, it’s not the bacteria itself - it’s the antibiotics meant to treat something else.

How Antibiotics Set the Stage for C. diff

Your gut is home to trillions of bacteria. Most of them are harmless. Many are essential. They help digest food, make vitamins, and keep harmful bugs in check. When you take antibiotics - especially broad-spectrum ones - they don’t just kill the bad bacteria. They wipe out the good ones too. That’s when C. difficile gets its chance.Not all antibiotics carry the same risk. Some are like sledgehammers. Others are more like scalpels. Research shows that certain classes are far more likely to trigger C. diff. Piperacillin-tazobactam, a common IV antibiotic used in hospitals, has been linked to more than double the risk of infection compared to other drugs. Carbapenems and later-generation cephalosporins like ceftriaxone are also high-risk. Even clindamycin, a drug often prescribed for skin infections, is one of the worst offenders.

On the flip side, tetracyclines like doxycycline are much safer. They don’t disrupt the gut as badly. The longer you’re on a high-risk antibiotic, the worse it gets. Each extra day of treatment raises your risk by 8%. And it’s not just the first week. The danger spikes after 14 days. That’s why doctors are now told to review antibiotics every 48 to 72 hours. If the infection isn’t bacterial, or if a narrower drug will do, stop the broad-spectrum one.

But here’s the twist: not everyone who takes antibiotics gets C. diff. Some people carry the bacteria without symptoms - they’re silent carriers. For them, antibiotics don’t increase their risk much. But for the rest of us? Antibiotics are the trigger. The CDC calls this an "urgent threat" because it’s preventable - and it’s happening far too often.

Why Recurrent Infections Are So Common

Many people think once you’re treated for C. diff, you’re done. Not true. About 20% of patients get it again. And once you’ve had one recurrence, your chances of another jump to 40-60%. Why?Standard treatments like vancomycin or fidaxomicin kill the active bacteria. But they don’t fix the broken gut ecosystem. The good bacteria are still gone. The environment is still wide open for C. diff to come back. That’s why recurrence is so common. Even if the diarrhea clears up, the underlying problem - the missing microbial balance - stays.

Some patients try probiotics. They hear about yogurt, kefir, or pills with live cultures. But the evidence is shaky. The Infectious Diseases Society of America says there’s not enough proof to recommend them. In fact, for people with weak immune systems, probiotics can cause dangerous infections. One small study looked at tapering antibiotics while using kefir - and saw results similar to fecal transplants. But it was tiny. Too small to change guidelines.

That’s why doctors now look beyond antibiotics. If you’ve had two or three recurrences, the next step isn’t another round of pills. It’s something that sounds strange - but works better than anything else: a fecal transplant.

Fecal Transplants: The Surprising Cure

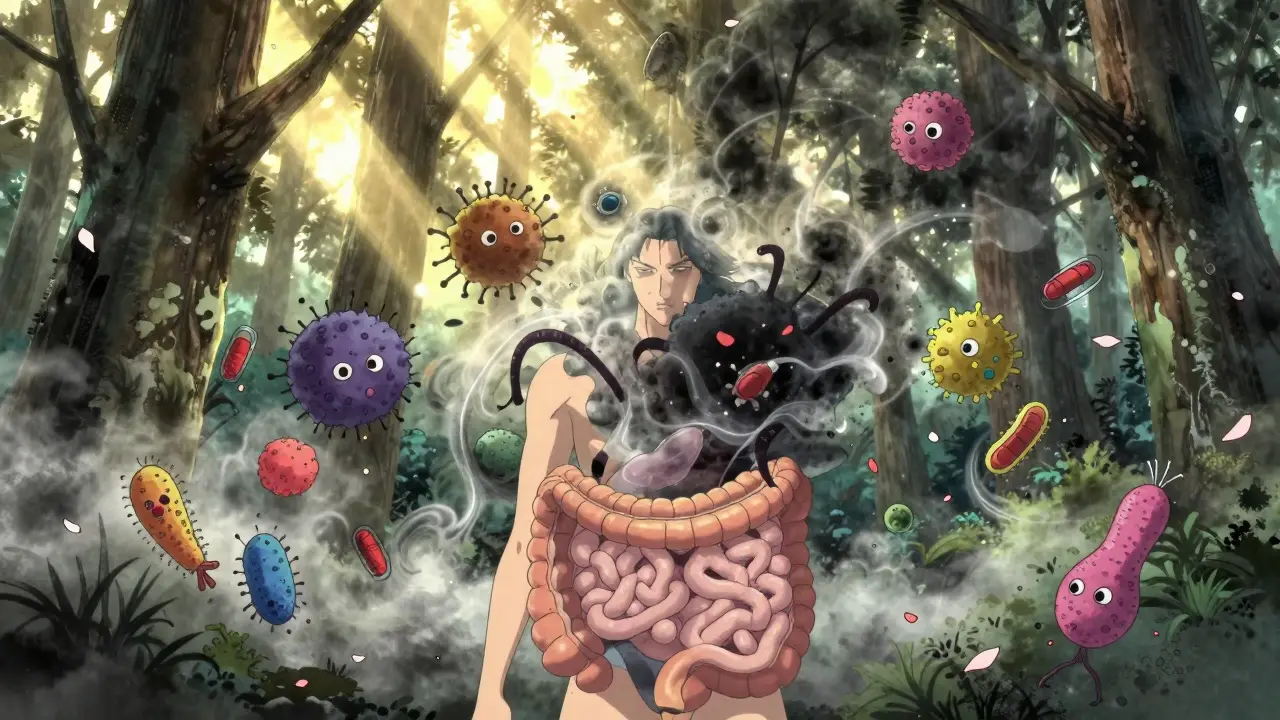

The idea sounds gross. You take stool from a healthy donor, process it, and put it into the colon of someone with C. diff. But it’s not new. Ancient Chinese medicine used "yellow soup" - fermented human feces - to treat food poisoning. Modern science just made it cleaner.In 2013, a landmark study in the New England Journal of Medicine changed everything. Patients with recurrent C. diff were split into two groups. One got vancomycin. The other got a fecal transplant via colonoscopy. The vancomycin group had a 31% success rate. The transplant group? 94%. One infusion cured most. A second one cured almost everyone.

Since then, dozens of studies have confirmed it. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) works in 85% to 90% of recurrent cases. It’s not magic. It’s biology. You’re not just killing bacteria. You’re restoring the whole community. The good microbes come back, outcompete C. diff, and rebuild the gut’s natural defenses.

There are different ways to deliver it. Colonoscopy is the most common - about 65% of procedures. Enemas are cheaper and less invasive. But the most popular now? Oral capsules. Freeze-dried stool in pill form. Patients swallow them at home. No sedation. No scope. Just a few pills. The FDA approved the first two standardized FMT products - Rebyota and Vowst - in 2022 and 2023. They’re not "raw" stool anymore. They’re regulated, tested, and ready for mass use.

Costs vary. A single FMT can run $1,500 to $3,000. But a hospital stay for recurrent C. diff averages $11,000. Multiply that by three recurrences, and you’re talking $33,000. FMT isn’t just more effective. It’s cheaper in the long run.

Who Gets FMT - and When

FMT isn’t for everyone. It’s not the first line of treatment. Doctors still start with antibiotics - usually fidaxomicin over vancomycin, because it has a slightly lower recurrence rate. Bezlotoxumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks one of C. diff’s toxins, can be added to reduce relapse by 10%.But if you’ve had three or more recurrences, FMT is the clear next step. Guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association and the Infectious Diseases Society of America both recommend it. Some hospitals even offer it after two recurrences if the patient is struggling.

Donors are screened like blood donors - but tighter. They’re tested for HIV, hepatitis, parasites, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and even gut disorders. The stool is processed in a lab, filtered, and tested again. No one gets a transplant from a friend or family member unless they’ve gone through the full screening. That’s because of a scary case in 2019: two immunocompromised patients got FMT from the same donor and died from a drug-resistant E. coli infection. Since then, safety protocols have gotten stricter.

There’s also a new wave of research. Scientists are now developing targeted microbiome therapies - pills with specific strains of bacteria, not whole stool. SER-109, a capsule made from purified bacterial spores, showed 88% effectiveness in a large trial. It’s not yet FDA-approved, but it’s the future: no "yuck factor," no donor dependence, just precise microbial medicine.

What You Can Do to Prevent C. diff

If you’re healthy and not in the hospital, your best defense is simple: don’t take antibiotics unless you really need them. Viral infections - colds, flu, most sore throats - don’t respond to antibiotics. Yet they’re still overprescribed. Ask your doctor: "Is this bacterial? Do I really need this?"If you’re in the hospital, ask if you can switch from a broad-spectrum antibiotic to a narrower one. Ask how long you’ll be on it. And if you start having diarrhea - especially after starting antibiotics - tell your doctor right away. Don’t wait. C. diff can turn deadly fast.

For those with recurrent infections, FMT is no longer experimental. It’s standard care. And it’s working. People who were stuck in a cycle of relapse - antibiotics, diarrhea, relapse, antibiotics - are getting their lives back. One patient on a medical forum wrote: "I had five recurrences. I was terrified to leave the house. After FMT, I haven’t had a single symptom in two years. It’s like my gut was reborn."

The goal now isn’t just to treat C. diff. It’s to prevent it. Antibiotic stewardship - using the right drug, at the right dose, for the right time - is the most powerful tool we have. And for those who’ve already been hit hard, FMT isn’t just a last resort. It’s a lifeline.

Anu radha

December 18, 2025 AT 01:48This made me think about my mom. She took antibiotics for a sinus infection and ended up in the hospital with C. diff. I had no idea it could happen like that. So many people just pop pills without knowing the risks.

Victoria Rogers

December 19, 2025 AT 02:35USA has the best hospitals and still this happens? Must be all the liberal doctors overprescribing. In my day we just toughed it out. Now everyone wants a pill for a sneeze.

Nishant Desae

December 20, 2025 AT 18:43I remember when my uncle had three recurrences of C. diff after being on antibiotics for pneumonia. He was so weak, couldn’t even walk to the bathroom. Then they did the fecal transplant and he was like a new man. I swear, it’s like giving your gut a second chance. People need to hear this more. It’s not magic, it’s science that works. And honestly, if we can use poop to save lives, maybe we need to stop being so grossed out and start being grateful.

Jody Patrick

December 22, 2025 AT 15:08Don’t forget that probiotics aren’t useless-they just aren’t enough on their own. I work in a clinic and we’ve seen people recover faster when they take probiotics *with* antibiotics, not after. It’s not a cure, but it helps the gut hang on.

Radhika M

December 24, 2025 AT 05:11My sister had a C. diff infection after a hip surgery. They gave her vancomycin for weeks. She lost 20 pounds. Then they did the capsule FMT. She was back to cooking curry for us in two weeks. No more fear of bathrooms. No more isolation. It’s not just treatment-it’s freedom.

Philippa Skiadopoulou

December 25, 2025 AT 15:04The evidence for FMT is robust. Regulatory approval of Rebyota and Vowst marks a turning point in microbiome-based therapeutics. Standardization reduces risk and improves accessibility. This is medicine evolving.

Pawan Chaudhary

December 27, 2025 AT 13:15Man, I’m so glad this is getting attention. My cousin was on antibiotics for a tooth infection and ended up in ICU. Now she’s fine after FMT. Just shows how amazing our bodies are when we let them heal right. Keep sharing this stuff!

Linda Caldwell

December 29, 2025 AT 08:42Antibiotics are like using a flamethrower to kill a mosquito. We need smarter tools. FMT isn’t gross-it’s genius. And those new pills? They’re the future. No more weird tubes or colonoscopies. Just swallow and heal. I’m telling my doctor to keep me updated.

CAROL MUTISO

December 29, 2025 AT 13:45Oh great, so now we’re transplanting poop like it’s a TikTok trend. Next they’ll be selling ‘gut glow’ smoothies with donor stool powder. At least the old-school way was honest-you knew you were eating shit. Now it’s FDA-approved and labeled ‘microbial restoration.’ How’s that for corporate magic?

Erik J

December 29, 2025 AT 16:41Is there data on long-term microbiome changes after FMT? Like, does the donor’s microbiome persist? Or does the recipient’s original flora eventually return?

BETH VON KAUFFMANN

December 31, 2025 AT 05:29Let’s be real-FMT is just a band-aid on a systemic failure of antibiotic stewardship. We’re treating the symptom, not the disease of medical overreach. And don’t get me started on the commercialization of fecal matter. This is biotech capitalism at its finest: turning biological waste into a $3K product.

Martin Spedding

January 1, 2026 AT 06:24Why are we even still debating this? People are DYING. And some of you are still making poop jokes? Grow up. This is life or death.

Steven Lavoie

January 1, 2026 AT 12:26Back home in Nigeria, my grandmother used fermented plant matter to treat stomach sickness. No labs, no pills-just tradition. Now science is catching up. FMT isn’t strange-it’s ancient wisdom with better sanitation. We should honor both.