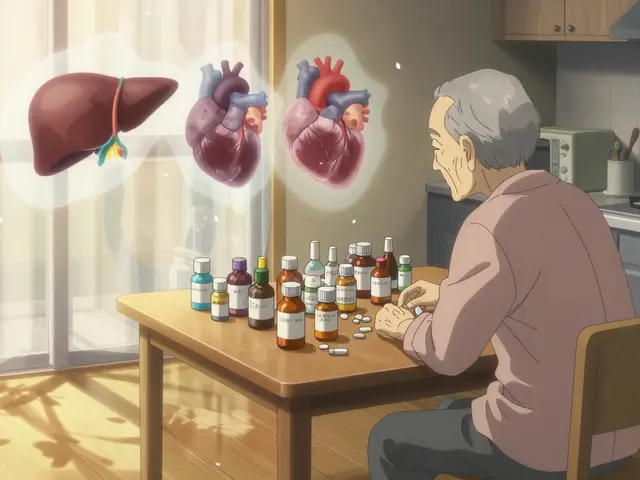

When a new drug hits the market, the work isn’t over. In fact, that’s when the real safety monitoring begins. The FDA doesn’t just approve a medication and walk away. It keeps watching - closely, continuously, and with increasingly advanced tools - to catch problems that clinical trials missed. Why? Because clinical trials involve thousands of people over months or a few years. Real life involves millions of people over decades, with different health conditions, other medications, and unpredictable behaviors. Something rare in a trial can become common in the real world. That’s why the FDA’s postmarket drug safety system is one of the most complex and critical public health operations in the country.

How the FDA Finds Problems After Approval

The FDA doesn’t wait for people to get hurt. It uses two main approaches: passive reporting and active surveillance. Passive reporting means waiting for someone to tell them about a problem. That’s where the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) comes in. Since 1969, FAERS has collected over 30 million reports of side effects, medication errors, and product issues. These come from doctors, pharmacists, patients, and drug manufacturers. By law, companies must report serious side effects within 15 days. But here’s the catch: most reports come from healthcare providers. Patients? They barely report at all. One study found only 6% of FAERS reports came from patients themselves. That’s a huge blind spot.

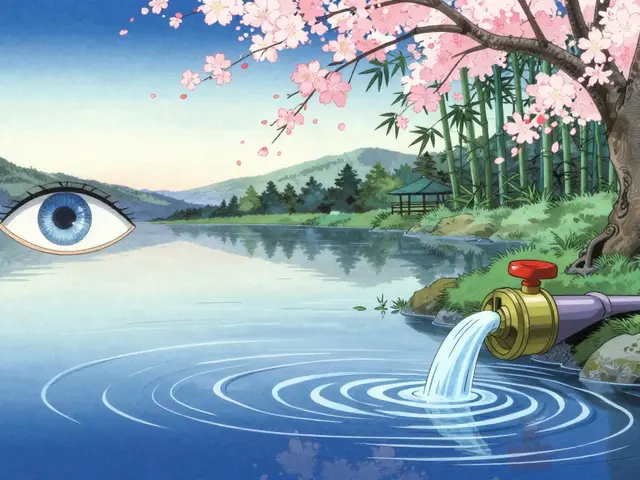

Active surveillance is where things get smarter. Instead of waiting, the FDA goes looking. The Sentinel Initiative, launched in 2008, pulls data from electronic health records, insurance claims, and hospital systems covering over 300 million people. It’s like having a national health dashboard that updates in near real-time. If a new diabetes drug suddenly shows a spike in heart failure cases among users in Texas, Sentinel can spot it before FAERS even gets a single report. This isn’t theory - it’s how the FDA found the link between certain painkillers and rare kidney injuries years before they were widely recognized.

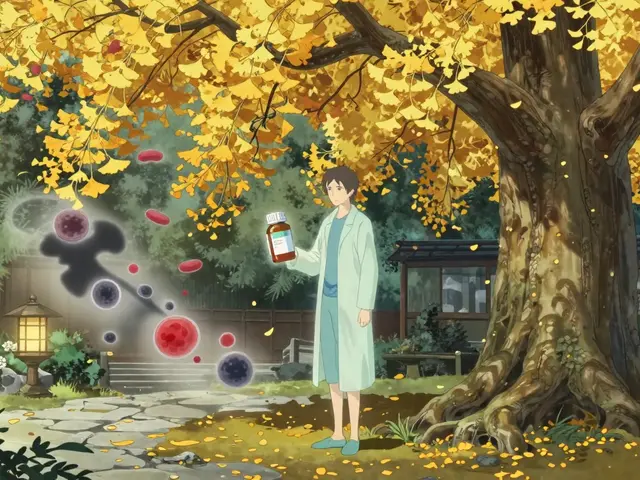

The Tech Behind the Scenes

Raw data doesn’t help unless you can make sense of it. That’s where tools like InfoViP come in. Introduced in 2019, InfoViP uses artificial intelligence to scan thousands of reports at once. It looks for patterns: unusual combinations of symptoms, spikes in reports after a drug’s launch, or side effects that show up more often than expected. Before InfoViP, it took an average of 14 months to detect a serious safety signal. Now, it’s down to just over six months. The system also cuts down on false alarms - the number of misleading signals dropped by 19% since 2018.

Statistical methods like Empirical Bayes Screening and Proportional Reporting Ratio help separate noise from real danger. For example, if 100 people taking Drug A report nausea, and 10,000 people taking Drug B report nausea, that’s normal. But if 100 people taking Drug A report a rare liver condition that only shows up in 1 out of 100,000 people normally? That’s a red flag. The system flags it automatically, and a team of epidemiologists, pharmacologists, and medical officers digs deeper.

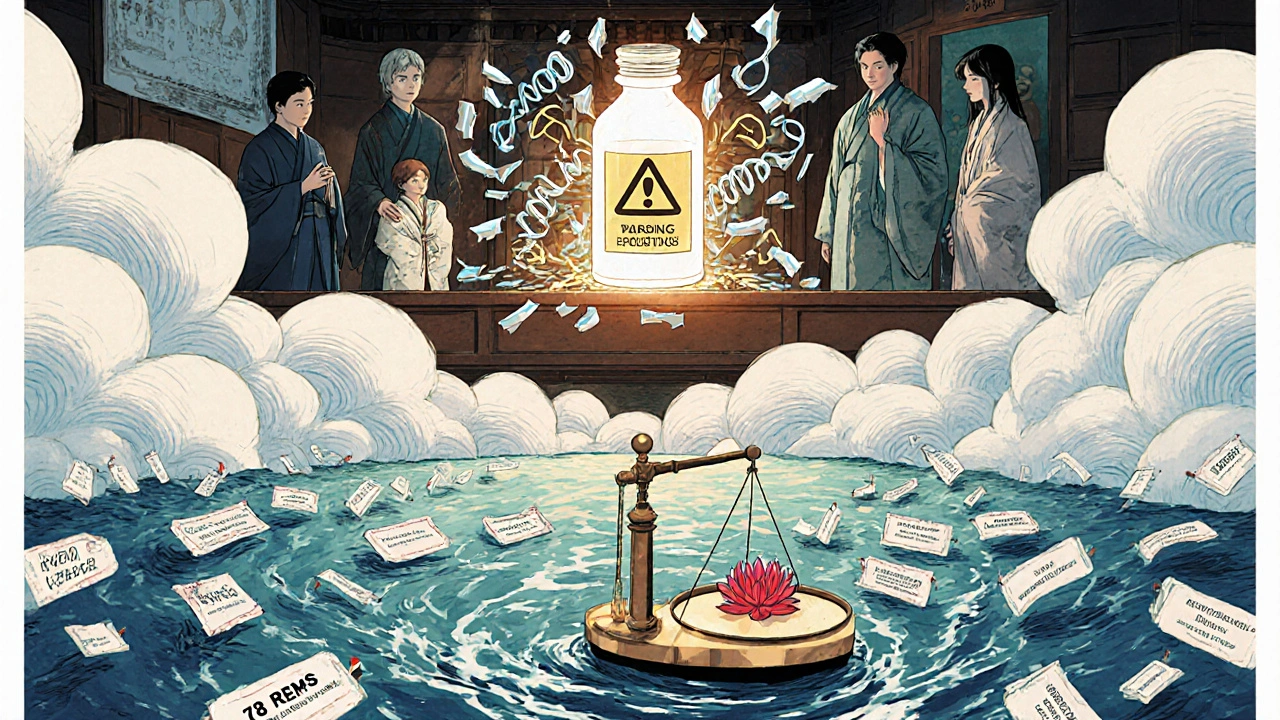

What Happens When Something Goes Wrong?

Spotting a problem is only half the battle. The FDA has to act - and fast. If a drug shows signs of causing serious harm, the agency can do several things. It can update the drug’s label to warn doctors and patients. It can require a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS), which might mean special training for prescribers, restricted distribution, or mandatory patient monitoring. As of early 2024, 78 drugs in the U.S. had active REMS programs. These often apply to drugs like blood thinners, cancer treatments, or powerful painkillers where the risk is high but the benefit is too important to withdraw.

In extreme cases, the FDA can pull a drug off the market. That’s rare - fewer than 10 drugs are withdrawn each year - but it happens. In 2021, a popular weight-loss drug was removed after multiple reports of severe liver damage. The FDA didn’t wait for hundreds of cases. Sentinel flagged an early spike. FAERS confirmed it. Within weeks, the drug was off shelves.

The Gaps and the Challenges

For all its strengths, the system isn’t perfect. The biggest problem? Underreporting. Studies show that only 1% to 10% of actual adverse events are ever reported. Why? Because doctors are busy. Patients don’t know how to report. And some side effects - like fatigue, brain fog, or mood changes - are hard to link directly to a drug. One oncologist on Reddit said she’d only submitted three reports in five years, even though she saw more. She didn’t feel it made a difference.

Another issue: small drugs get ignored. If a medication is only used by 50,000 people, it can take nearly five years to detect a safety signal. That’s dangerous for patients with rare diseases who rely on those drugs. The FDA has started targeting these gaps with special programs, but progress is slow.

Then there’s the staffing problem. The FDA’s Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology is operating at 82% capacity. With over 10,000 drugs on the market and new therapies like gene treatments arriving faster than ever, the team is stretched thin. Experts warn that without more funding and staff, the system could buckle under the weight of innovation.

How Patients and Providers Can Help

You don’t have to be an FDA employee to protect drug safety. If you or someone you know has a serious side effect, report it. It takes less than 17 minutes through the MedWatch portal. You don’t need a diagnosis. You don’t need proof. Just describe what happened, when, and what drug you were taking. Even if it seems minor, it might be the first clue in a pattern.

Doctors and pharmacists should make reporting part of their routine. The FDA has tools to make it easier - automated alerts in electronic health records, pre-filled forms, and even phone hotlines. But too many providers still don’t know about them. A 2022 survey found that 41% of healthcare workers had never heard of MedSun, the program that recruits providers to report device-related injuries. That’s a missed opportunity.

Patients with rare diseases need better education. Only 28% of rare disease patients know how to report side effects, even though they’re often the most vulnerable. Advocacy groups are stepping in, but the FDA needs to do more to reach them directly - through patient portals, support networks, and community health centers.

What’s Next for Drug Safety?

The future is data-driven. In 2024, the FDA launched Sentinel 2.0, which now includes genomic data from 10 million people. That means they can start asking: Does this side effect only happen in people with a certain gene? Could we one day predict who’s at risk before they even take the drug?

A blockchain-based reporting pilot is coming in 2025. It could make reports more secure, tamper-proof, and traceable. And by 2025, the FDA will require every high-risk drug to have an active surveillance plan - up from 68% in 2020.

By 2030, experts predict that 75% of safety signals will come from active surveillance, not passive reports. That’s a huge shift. It means fewer surprises, faster responses, and better protection for patients.

The system isn’t flawless. But it’s evolving - and it’s working. Every year, it prevents thousands of injuries and saves lives. The real question isn’t whether the FDA is doing enough. It’s whether the public and healthcare system will keep pushing it to do more.

How long does it take the FDA to detect a drug safety problem after approval?

It varies. For widely used drugs, the FDA can detect a safety signal in as little as 2 years. For drugs with fewer than 100,000 users, it can take nearly 5 years. With the new Sentinel Initiative and AI tools like InfoViP, detection time has dropped from 14 months to about 6 months on average for high-risk drugs.

Can patients report adverse drug reactions directly to the FDA?

Yes. Patients can report side effects directly through the FDA’s MedWatch portal. While most reports come from healthcare providers, patient reports are just as valuable. The FDA encourages anyone who experiences a serious side effect - even if they’re unsure if the drug caused it - to submit a report. It only takes about 17 minutes.

What’s the difference between FAERS and Sentinel?

FAERS is a passive system that collects voluntary reports from doctors, patients, and drug companies. Sentinel is an active system that analyzes real-time health data from millions of patients across hospitals and insurance databases. FAERS tells you what people say happened. Sentinel shows you what actually happened in real-world populations.

Why do some drugs get REMS programs and others don’t?

REMS programs are required for drugs with serious known or potential risks that need extra controls to ensure benefits outweigh risks. Examples include drugs that can cause birth defects, liver failure, or severe allergic reactions. The FDA decides based on clinical trial data, postmarket reports, and expert review. As of 2024, 78 drugs had active REMS programs.

How often does the FDA pull a drug off the market?

Very rarely - fewer than 10 drugs per year. The FDA prefers to update labels or add safety requirements like REMS before removing a drug. Withdrawal only happens when the risks clearly outweigh the benefits and no other safety measures can reduce the harm. Most drugs stay on the market with updated warnings.

Ross Ruprecht

November 21, 2025 AT 17:04So basically the FDA is just waiting for people to die before they do anything? Cool.

Ragini Sharma

November 22, 2025 AT 09:29lol i reported my weird brain fog after that new sleep pill and got a auto-reply saying 'your report has been received' like it was a pizza order 🤡

Bryson Carroll

November 24, 2025 AT 08:48FAERS is a joke and everyone knows it. The system is designed to make you feel like you're helping while actually being ignored. The real problem? The FDA is just a glorified paper pusher with a budget bigger than your mom's credit card debt

Lisa Lee

November 25, 2025 AT 23:14Why are we trusting a government agency that can't even fix the VA? This whole thing is a farce. We need Canadian-style oversight. They actually do their job.

Manjistha Roy

November 27, 2025 AT 12:06It's important to remember that reporting side effects isn't just a formality-it's a lifeline for others. Even if you think it's minor, it might be the first clue that saves someone's life. Please, if you notice anything unusual, take those 17 minutes. It matters more than you know.

Javier Rain

November 28, 2025 AT 12:48Y'all are underestimating how much this system actually saves lives. Yeah it's not perfect but without Sentinel and AI tools like InfoViP, we'd be flying blind. I work in pharma and I've seen the data-early detection saves thousands. Keep pushing for better reporting, not just complaining.

Laurie Sala

November 29, 2025 AT 04:36But... but... what about the people who get hurt and don't even know it's the drug? I had a friend who developed tremors after six months... she thought it was stress... then she found out it was the antidepressant... and the FDA didn't even flag it until three years later... why does it take so long? Why? Why? Why?

Lisa Detanna

December 1, 2025 AT 02:22As someone from a country where drug safety is a luxury, I'm amazed at how much infrastructure the FDA has. It's not perfect, but it's leagues ahead of most places. Maybe instead of tearing it down, we should be helping it grow-funding, staffing, public education. Global health equity starts here.

Demi-Louise Brown

December 2, 2025 AT 18:08The postmarket surveillance system represents a significant advancement in public health infrastructure. While underreporting remains a concern, the integration of real-time data analytics has demonstrably improved signal detection timelines. Continued investment in technological and human capital is essential to sustain this progress.

Matthew Mahar

December 3, 2025 AT 13:32wait so you're telling me i could've saved my cousin from liver failure if i just clicked a button on a website? i feel like an idiot. i thought it was just for doctors. i had no idea patients could report. i'm gonna go do it right now

John Mackaill

December 4, 2025 AT 19:38It's fascinating how much data is being aggregated now. But I wonder if we're over-relying on algorithms. Human intuition still matters-especially when symptoms are vague, like fatigue or brain fog. AI can spot patterns, but it can't listen to a patient's story.

Adrian Rios

December 6, 2025 AT 14:00Let's be real-this whole system works because of the quiet heroes: the pharmacists who notice a spike in reports, the nurses who document symptoms in EMRs, the patients who finally say 'this isn't right' after being dismissed for months. The tech is cool, sure, but it's the people who make it work. We need to thank them more and demand better support for them. They're the real frontline.

Casper van Hoof

December 7, 2025 AT 21:51The tension between innovation and safety is the central paradox of modern pharmacology. We demand faster cures while demanding perfect safety. The FDA walks a razor's edge between precaution and paralysis. Perhaps the real question is not whether the system is flawed but whether society is willing to accept the inherent uncertainty of medical progress

Richard Wöhrl

December 8, 2025 AT 09:49Just wanted to add-many patients don't report because they don't know what counts as 'serious.' If you had a rash that lasted a week? Report it. If you felt dizzy every time you stood up? Report it. If you suddenly couldn't remember your kid's name? REPORT IT. The FDA doesn't need you to diagnose it-they need you to describe it. No judgment, no proof needed. Just your truth. And that's powerful.